“That’s not fair!” is a common refrain in preschool classrooms. Children often struggle to share favorite toys, take turns, and are prone to saying hurtful things such as “I don’t want to play with you,” or “I don’t want to be your friend.” As educators, we do our best to mediate hurtful situations during which children feel judged or left out. However, getting the concept of fairness to stick can be tricky.

Fairness is an abstract concept, and young children are concrete thinkers. The Resource for Early Learning, a project of the Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care and the WGBH Educational Foundation, say, “Young children are often egocentric thinkers, and tend to see the world from their own perspective. So, when they say ‘That’s not fair,’ it’s because they don’t like the outcome.”

Fairness is an abstract concept, and young children are concrete thinkers. The Resource for Early Learning, a project of the Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care and the WGBH Educational Foundation, say, “Young children are often egocentric thinkers, and tend to see the world from their own perspective. So, when they say ‘That’s not fair,’ it’s because they don’t like the outcome.”

What can we do to support children in developing empathy and sensitivity toward others’ emotions? Below are six strategies to help you make fairness more understandable for children in your learning space.

1. Fair vs. unfair sort.

Since we know children are concrete thinkers, make fairness concrete by playing a simple sorting game. Print images of children in different play scenarios. Find several that show situations of fairness and unfairness (e.g., a child with lots of toys playing next to a child with none, children sharing toys, children at a snack table where everyone is enjoying the same treat, a child sitting alone on a playground watching a group of friends play, etc.). Make sure the images are age appropriate or show similar-aged children. Sit in a circle and spread out the images. Write “fair” and “unfair” on index cards. Invite children to sort the images under the correct cards. Talk about each scenario. Ask, “What makes this fair? What about this is unfair?” Support children in working through their reasoning and ask them to think about how unfair situations could be remedied.

2. Set a timer.

Every preschool setting has a coveted item—magnet tiles, trucks/cars, a character-based dress-up costume, a certain color of marker—the list goes on. For children who struggle with turn-taking, set a timer. Try to use a visual timer such as a  large hourglass or a Time Tracker, so children can monitor their play in accordance with the timer. Vary the length of the timer and talk with children about what length of time seems fair based on the total amount of time you have and how many children are interested in the item. Allow extra time when possible for well-liked items.

large hourglass or a Time Tracker, so children can monitor their play in accordance with the timer. Vary the length of the timer and talk with children about what length of time seems fair based on the total amount of time you have and how many children are interested in the item. Allow extra time when possible for well-liked items.

3. Teach division.

Initially, teaching division to preschoolers may seem just as foreign as teaching fairness, but there are simple ways to introduce the concept. Choose a favorite food of your group. It could be pizza, apples, or maybe even a special treat such as cake. Present the food, unportioned. Count the number of people in the room. Ask, “How can we divide this item so everyone receives the same size piece?” Remind children that everyone really likes this food, so you will want to be fair. Start to cut the item into pieces. After a few cuts, ask, “Is there enough for everyone? Is each slice the same size?” Continue in this way until there is piece for everyone (do your best to ensure the pieces are roughly the same size). Talk with children about this experience.

4. Everyone plays a part.

Classroom jobs play an important role in most preschool settings. Chances are if you do not have formal jobs for children in your learning space, they are helping with tasks in some way. Talk about the different responsibilities children  have. Why is each one important? What would happen if someone didn’t do his job? Test this out. If you have children who water plants or put away supplies, ask them to stop doing their jobs for a day or two. What happens to the plants? Can everyone work or eat or play safely with the supplies still out? Though children may not always enjoy their jobs or think they are fair, everyone needs to play his part for the space to be fun and safe.

have. Why is each one important? What would happen if someone didn’t do his job? Test this out. If you have children who water plants or put away supplies, ask them to stop doing their jobs for a day or two. What happens to the plants? Can everyone work or eat or play safely with the supplies still out? Though children may not always enjoy their jobs or think they are fair, everyone needs to play his part for the space to be fun and safe.

5. Praise the positive—excitedly and often!

It’s easy to remember to give children positive feedback when we’re in the middle of a learning experience or observing their creativity. Don’t forget to share your enthusiasm for a child’s honest efforts when he decides to share, apologize without prompting, etc. When you see children taking turns, or when you’ve successfully helped them understand that it’s time to take a turn, use their words, or offer apologies, get excited. You might say, “I know that sharing can be hard, but you did it!” Or, you might say, “Wow, you used your words, and Becca listened!” End challenging situations on a positive note, even if it means saying, “I know you’ll remember to use your words next time,” and offer a hug of support.

6. Encourage expression and ask questions.

When children are concerned about fairness or are being unfair, address it immediately. If a child is claiming all of the markers, find out why. Call attention to the children waiting to use the markers. How do they feel? Are they frustrated to have to wait? Make a plan for turn-taking. If a common item is causing frustration in your group, use a circle time to role-play sharing with that item. For example, if children consistently argue over the same book, model how they should ask for a turn with the book. Demonstrate how the child using the book should hand it to the next child. Give each child a turn to say, “May I read the book when you’re finished?” and  for another child to respond with, “Yes, I am finished with the book. You may have a turn now.” Though this modeling may seem redundant and take time, children will learn from this practice and repetition. Make these experiences a regular part of circle time to support children’s understanding of fairness and the language associated with fairness. When you hear a child saying, “I don’t want to play with you,” take time to dissect the situation. Children will often say this phrase when they mean something else. What has happened to make the child respond in this way? Did someone take a toy away from her, make a noise she didn’t like, or bump her accidentally? Sometimes children will “attack” the person and not the problem. Teach children to address problems by modeling appropriate language such as, “I didn’t like it when you bumped into me.” In this situation, the offending child knows to be careful with his body around others, rather than feeling left out for no obvious reason.

for another child to respond with, “Yes, I am finished with the book. You may have a turn now.” Though this modeling may seem redundant and take time, children will learn from this practice and repetition. Make these experiences a regular part of circle time to support children’s understanding of fairness and the language associated with fairness. When you hear a child saying, “I don’t want to play with you,” take time to dissect the situation. Children will often say this phrase when they mean something else. What has happened to make the child respond in this way? Did someone take a toy away from her, make a noise she didn’t like, or bump her accidentally? Sometimes children will “attack” the person and not the problem. Teach children to address problems by modeling appropriate language such as, “I didn’t like it when you bumped into me.” In this situation, the offending child knows to be careful with his body around others, rather than feeling left out for no obvious reason.

Books

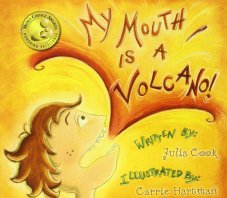

- My Mouth Is a Volcano by Julia Cook

- The Berenstain Bears: No Girls Allowed by Stan & Jan Berenstain

- The Greedy Triangle by Marilyn Burns

- The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi

- Little Red Hen by Paul Galdone

- Do Unto Otters: A Book About Manners by Laurie Keller

- It’s Mine! by Leo Lionni

- Stone Soup by Ann McGovern

- It’s Not Yours, It’s Mine! by Susanna Moores

- Pipsqueaks, Slowpokes, and Stinkers: Celebrating Animal Underdogs by Melissa Stewart

Back to blog listing